Recently, University of Leicester Archaeological Services (ULAS) had a couple of enquires about the link between King Leir and the Jewry Wall in Leicester – and so ULAS Project Officer Mathew Morris investigated…

One of Leicester’s most enduring legends is that of King Leir, the tragic king made famous by William Shakespeare’s titular play. Leir was a legendary king of the Britons whose story was first told by the chronicler Geoffrey of Monmouth in the early 12th century AD in his pseudohistorical Historia Regum Britanniae (History of the Kings of Britain).

In Monmouth’s original account (Book II, 10-14), which differs slightly from Shakespeare’s, King Leir ruled in Britain for 60 years in the late 9th / early 8th century BC (his death being recorded as 7 years before the founding of Rome in 753 BC). He was credited as the eponymous founder of a city built upon the River Soar, “called in the British tongue Kaerleir, in the Saxon, Leircestre”. Growing old and without a male heir, Leir decided to divide his kingdom between his three daughters, Goneril, Regau (Regan in later versions) and Cordelia. The elder daughters flattered the king and were duly rewarded with half his kingdom, whilst Cordelia refused to sweet-talk her father and was disinherited, eventually leaving Britain to marry a king of the Franks. At first Goneril and Regau treated their father with respect but eventually they rebelled and seized his entire kingdom, forcing him to flee to Cordelia in France. Cordelia led an army back to Britain, successfully overthrew her sisters and restored her father, who ruled a further three years before dying. Cordelia succeeded him and “buried her father in a certain vault, which she ordered to be made for him under the river Soar, in Leicester, and which had been built originally under the ground to the honour of the god Janus.”

To muddy the waters, despite its early Iron Age setting, Monmouth’s story utilised Roman deities, the post-Roman geopolitical landscape and medieval titles of nobility and the story has a distinctly post-Roman vibe. Clearly, Monmouth’s account is fictional, probably invented by the author himself who drew on a mixture of Welsh legends and historical anecdotes to concoct a narrative for Britain’s early history, starting with its settlement by Trojan refugees led by Brutus, a descendant of Virgil’s Trojan hero Aeneas. So how close to reality does the story come? What truths lie behind the narrative, and where did the story of King Leir come from in the first place?

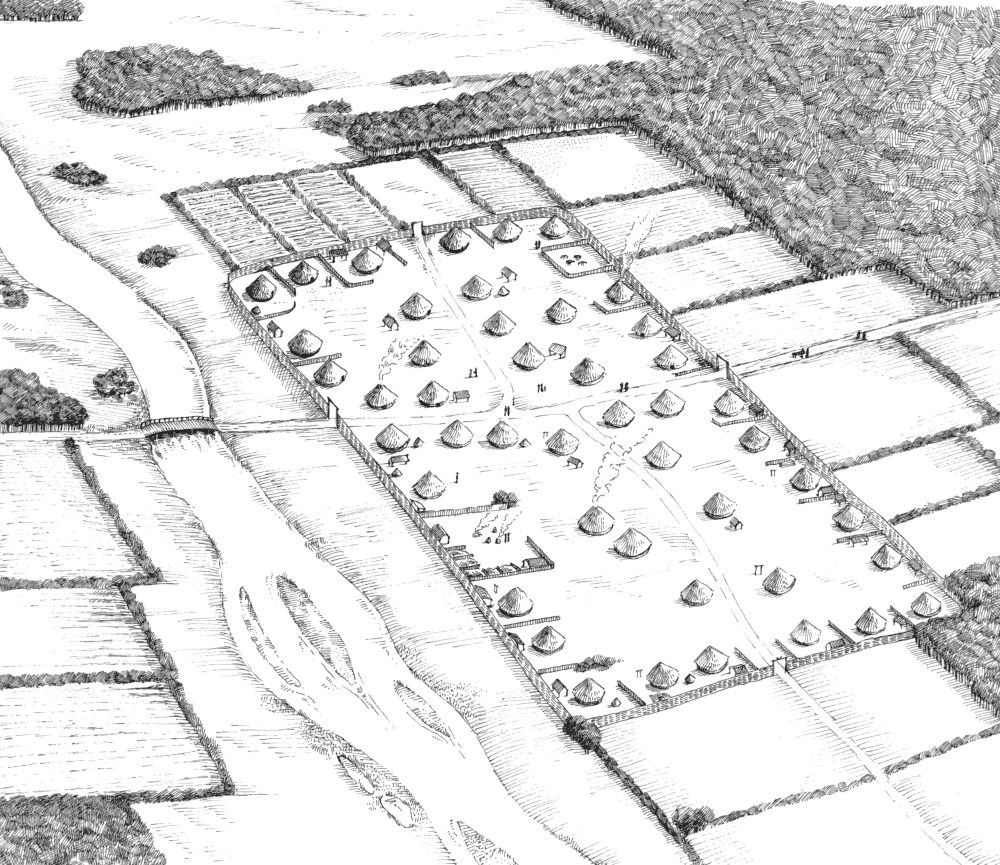

First, Leicester’s foundation. Archaeological excavations across the city have firmly established that the first permanent settlement at Leicester occurred a little over 2,000 years ago, during the 1st century BC, seven centuries later than Monmouth claimed. This first settlement was sited over a ten-hectare area along the east Bank of the River Soar near St Nicholas Circle in the modern city. The settlement was regionally important, with extensive contacts with the rest of Britain and the Continent and was probably a royal centre (as Monmouth intimates) for a group of the Corieltavi, a loose federation of peoples which controlled much of the East Midlands during the late Iron Age but not all Britain.

It was not called Kaerleir. The earliest recorded name for Leicester, written in Ptolemy’s Geographia (c.AD 150), was Ratae, thought to be a Romanised Celtic (British) word meaning ‘ramparts’. Later in the Roman period it became Ratae Corieltavorum and it was still described as Rate Corion Eltauori in the early 8th century AD. By the end of the 8th century something had changed, and it had come to be known as Legorensis Civitatis. It wasn’t until the early 9th century, however, that it was first called Kaerlier (by the Welsh monk Nennius) and it wasn’t known as Leircestre until the 11th century (the Domesday Book being the earliest use of that spelling) – in between it was Legraceastre, meaning ‘the fortified Roman town of the people of the Legra’.

Some authors have attempted to link King Leir with the god Lir, the divine personification of the sea in Irish mythology, or the Welsh mythological figure Llŷr. Following this line of thought, Leir was suggested to be the pre-English name for the River Soar, referencing a water god from Celtic mythology who was popular in the region and who subsequently evolved into the Leir of Leicester legend.

This particularly resonated following the discovery, during the construction of Vaughan Way in 1964, of a fragment of Roman relief, possibly part of an altar, depicting a bearded deity wearing a sleeveless robe and a fishman’s cap, interpreted as a river- or water-god. Some have attempted to claim this as a representation of the water-god Leir, although the Roman god Oceanus is more commonly attributed and other mythological figures such as Odysseus and Hephaestus are equally plausible. A column drum found nearby, carved with fish scales, also conjured images of water-themed worship but was more likely to have come from a Jupiter column. In these monuments, which are well known in the north-western provinces of the Roman Empire, a scale-decorated column crowned with a statue of Jupiter, usually on horseback, was often associated with a public building, which is consistent with the Leicester column being found near the town’s macellum (market hall).

Another possibility, like the River Loire in France, is that Legra comes from the Latinised Celtic (Gaulish) word liga, meaning ‘silt’ or ‘alluvium’. This would amply describe the shallow, slow-moving river that flows through Leicester. Unfortunately, the word Soar is also thought to be a pre-English river-name, meaning ‘flow of water’, and could have always been the name of the river. It has also been argued that Legra is not pre-English at all but derives instead from the Old English leger, which could mean either ‘grave’ or ‘lair’. If this is the case, Legraceastre might better be described as ‘the cemetery at the fortified Roman town’ or ‘the camp at the fortified Roman town’.

The little we do know suggests that Legra was adopted as a name by a group of post-Roman people living in the area around Leicester, most likely in the 8th century AD when the town’s name changed. In Old English Legore or Ligore means ‘the people of the Legor / Ligor’. What is less clear is what this word refers to. Is it another name for the River Soar as already suggested? Does it reference the tributary of the Soar to the west of the town which is still called the Leire today, or the village of the same name? The long-maintained belief that Legore is a folk-name derived from a river-name must be treated cautiously and this discussion is not helped by the various phonetic spellings of the word. Take surviving 10th-century charters for instance, which variously use Legra-, Ligera-, Ligra-, Ligre-, Ligere– and Ligranceastre.

So, myth busted! Use of the word Leir does not pre-date the 8th century AD and it is probably a corruption of the word Legra, which is more likely to have a geographical meaning than a mythological one. King Leir did not found a city at Leicester in c. 800 BC and probably never existed, being the construct of a medieval chronicler who was trying to fashion a coherent origin story for Britain out of fragments of disjointed myths and traditions. This does not mean that there is no archaeological significance to the legend, however. One curious aspect is Cordelia’s burial of her father in a vault beneath the River Soar, dedicated to the Roman god Janus.

It has long been suggested that this part of the story was inspired by the arches and recesses of the Jewry Wall, the still-standing remains of the Roman town’s public baths. The Jewry Wall has in the past been called the ‘Temple of Janus’, its size presumably leading some antiquaries to believe it was the remains of a Roman temple. Others, attempting to explain the name have suggested that Janus came from the Latin word janua meaning ‘gateway’. This tied in with a common misconception, held from the 18th-century up to the site’s excavation by Kathleen Kenyon in the 1930s, that the wall was the remains of the town’s west gate.

When and why the monument got this name remains unclear but the belief that it was one of the town gates cannot have been held in the 12th century because the Roman town wall and gate still stood, at this time, along the riverbank 100m further to the west. It is more likely that the site’s association with Janus is because of Monmouth’s story and not the inspiration for it.

This masks an important observation about the town’s appearance in the 12th century, however. Our popular perception of a medieval town is one of tightly packed timber-framed buildings with little stonework used except in the more important buildings – churches, castles, monasteries, and the homes of a few wealthy elite. This appears to be true of Leicester, where good sources of local building stone were scarce but ample timber was readily available nearby in Leicester Forest.

Now, however, there is a growing body of evidence from excavations in the town that the walls of many Roman buildings were still standing in the 11th and 12th centuries, influencing the routes of streets, which had to weave around the ruins, with some of the visible stonework probably incorporated into medieval buildings – the Jewry Wall itself is thought to have originally survived because it formed the west end of St Nicholas church and continued to survive because other buildings were built up against it. It was not until the later 12th century, when the castle and churches were rebuilt in stone, that widescale quarrying cleared the Roman ruins and recycled much of the remaining masonry.

Had Geoffrey of Monmouth visited Leicester, and his topographical knowledge suggests he probably did have some familiarity with the town, he would have found an eclectic blend of medieval vernacular and Romanesque architecture incorporating a scattering of older Roman masonry styles. Could it be then, that his inclusion of a stone vault dedicated to a Roman god was an attempt to rationalise the Roman ruins still standing in the town?

We will never know for sure, but there is often a grain of truth hidden in even the most fantastical of historical works and Monmouth may have been recording Leicester’s very first ‘archaeological’ discovery.

Featured image: Cordelia’s Portion by Ford Madox Brown (1866).

Source: ULAS