by Wayne Perkins

See also (New Discoveries Made in Worcestershire During Graffiti-Fest 2022 – Ritual Protection Marks & Ritual Practices)

Last year I was approached by the Simon de Montfort Society to give a talk on the medieval and historic graffiti recently discovered in the churches and medieval buildings of the former Evesham Abbey Precinct. It was then opened up to include the surrounding churches in Worcestershire.

It was also agreed that it would be an interesting proposition to include a practical element to the proceedings by organising a guided walk around the sites whereby those attending would bring their own torches to hunt for graffiti themselves. In between these two events a second talk was undertaken for The Badsey Society in the setting of St James’s church which allowed for a post-talk exploration of the building. Both the Evesham Abbey Trust and the Evesham Almonry Museum became involved with the weekend creating full itinerary![1]

The more general aim, therefore, was to encourage community participation and hopefully set in motion a number of local graffiti surveys by the resident history groups or individuals in the area. Proposed research agendas could include an accurate survey / recording exercise of the graffiti in a more thorough manner that has been hitherto possible. Although 3D-scanning may be financially prohibitive, research into spatial analysis of the marks and a chronological analysis of the buildings fabric could be undertaken fairly easily. In many ways, graffiti surveys lend themselves to community-based projects as usually the buildings are accessible to people of all abilities and the post-survey analysis is certainly something anyone could attempt.

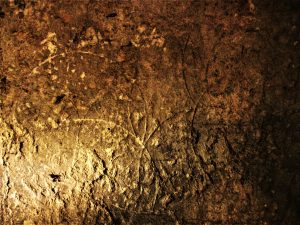

Both the churches in Evesham and Badsey – along with others from the County of Worcestershire – had produced a corpora of almost all of the most ‘common’ types of graffiti – crosses, initials and dates, compass-drawn circles and Marian Marks – whilst also producing some ‘anomalies’ – a cross pattée and several ‘chalice’ motifs at Badsey as well as a shoe outline, Sacred Monogram and several ‘dagaz’ runes from Evesham.

The study of medieval graffiti has been in the ascendant recently, with popular books published on the subject. These mainstream publications have helped to disseminate the new interpretative frameworks and ideas which are the culmination of the last thirty years of academic research into medieval inscriptions. The new paradigm shift in graffiti research has been due to a convergence of the disciplines of field archaeology, historic buildings recording and church archaeology.

The re-evaluation of medieval graffiti has revealed many more subtleties and diverse meanings than hitherto imagined. Graffiti can span the entire medieval period but appears to peak in secular buildings between AD 1550 –1800 (Early Modern Period) such as in domestic housing, farms and their outbuildings.

There are many categories of graffiti now recognised, including masons’ marks, devotional and memorial inscriptions and a whole range of apotropaic symbols now believed to represent elements of ritual building protection.[2] These latter symbols are often concentrated around thresholds including doors, windows and fireplaces. Additionally, they are found where repairs or alterations have been made – such as when a chimney stack had been incorporated into an earlier building – or in cases where the ‘integrity’ of the building had been temporarily breached.

The author presented his results of a preliminary survey undertaken in Worcestershire following the English Heritage Grade II protocols usually used for non-intrusive photographic surveys. These initial findings required further elaboration along with an attempt to fine-tune the interpretations thus far presented – which would be within the competence of most individuals/groups. Further, the study of church records would enable the possible identification of the individuals who had carved their initials and dates recorded amongst the corpora but which so often prove to be just as elusive as the more obscure symbols found etched into the walls.

[1] The buildings included as part of the ‘Evesham Abbey Precinct’ were All Saints & St Lawrence’s churches, The Abbey Gatehouse, The Almonry Museum, Lichfield’s Bell Tower & the Cloister Arch.

[3] These have been dubbed ‘witch marks’ in the popular press which is erroneous. Apotropaic is the correct terminology. The term ‘witch mark’ was used by Witchfinders’ conducting strip searches of their unfortunate victims whereby any unusual ‘mark’ found upon their body would have identified them as a witch.

Practical Magic

- The first priority is to choose a research agenda for the survey, be it an individual building or group of buildings. In advance of the survey, archaeological and architectural descriptions of the fabric of each of the buildings should be sourced and collated. A full understanding of the building’s architectural evolution will be key to the interpretative model.

- The next step is to record each of the marks as completely as possible along with their locations. Full access to the buildings should be sought for those areas not normally open to the public.

- A strong torch (preferably of an L.E.D. type) is required to apply ‘raking light’ to the walls and each mark should be described and dimensions taken. Photography in darker recesses will require a tripod and a photographic scale should always be included in reference shots.

- The English Medieval Graffiti survey provide pro forma recording sheets which also carry descriptions and interpretations of some of the marks to get you started.

- Once you have created a corpus of graffiti it can then be subject to various types of basic data examination such as categorization and spatial analysis which may illuminate graffiti ‘hot spots’ – It is now understood that there is no such thing as a ‘complete’ corpus as many marks will have been covered in limewash or plaster, weathered out or had elements of the building’s fabric removed/restored/reinstated.

- Once done there may be other cultural or historical considerations that can be woven into the narrative to create a rounder profile of the graffiti that can then be described within its local, regional and national contexts.

Selected bibliography

Binding C J & Wilson, L J (2004) ‘Ritual Protection Marks in Goatchurch Cavern, Burrington Combe, North Somerset’ in, Proceedings of the University of Bristol Spelaeological Society No.23, p.119-133

Champion, M (2017) ‘English Medieval Graffiti Survey: Volunteer Handbook.’ http://www.medieval-graffiti.co.uk/Volunteer%20Handbook%20NMGS.pdf

Easton, T (2015) ‘Like The Circles That You Find…’ in, Society for the Protection of Ancient Buildings Magazine. Winter 2015.

Evans, I (2010) Touching Magic: Deliberately Concealed Objects in Old Australian Houses and Buildings https://www.academia.edu/659306/Touching_Magic_Deliberately_Concealed_Objects_in_old_Australian_Houses_and_Buildings

Hoggard, B (2021) Protection Marks in Buildings & Other Buildings

Manning, C (2014) ‘Magic, Religion & Ritual’ in, Historical Archaeology 48 (3) pp.1-9.

Merrifield, R (1987) ‘The Archaeology of Ritual & Magic.’ BT Batsford Ltd, London

Perkins, W (2020) ‘Sealed Against Spirits: The Strange Case of Ritual Protection Marks & Practices at Ightham Mote, Kent.’ Treadwells Books.

Robson-Glyde, S (2008) Abbey Gate, Merstow Green, Evesham: Building Recording & Watching Brief. Worcester County Council: Historic Environment & Archaeology Service https://archaeologydataservice.ac.uk/archiveDS/archiveDownload?t=arch-952-1/dissemination/pdf/fieldsec1-239454_1.pdf

Internet Resources

Ritual Protection Marks & Ritual Practices https://ritualprotectionmarks.com

Raking Light https://rakinglight.co.uk/uk/

English Medieval Graffiti www.medieval-graffiti.co.uk

Worcestershire Medieval Graffiti Project https://worcestershiremedievalgraffiti.files.wordpress.com/2016/11/volunteer-handbook.pdf

Video Lecture on Protection Marks with Brian Hoggard

Facebook Live Video | Protection Marks in Churches and Other Buildings – with Brian Hoggard