Durrington Walls is one of the largest known henge monuments measuring 500m in diameter and thought to have been built around 4,500 years ago. Measuring more than 1.5 kilometres in circumference, it is surrounded by a ditch up to 17.6m wide and an outer bank c.40m wide and surviving up to a height of 1 metre. The henge surrounds several smaller enclosures and timber circles and is associated with a recently excavated later Neolithic settlement.

Several remote sensing techniques used

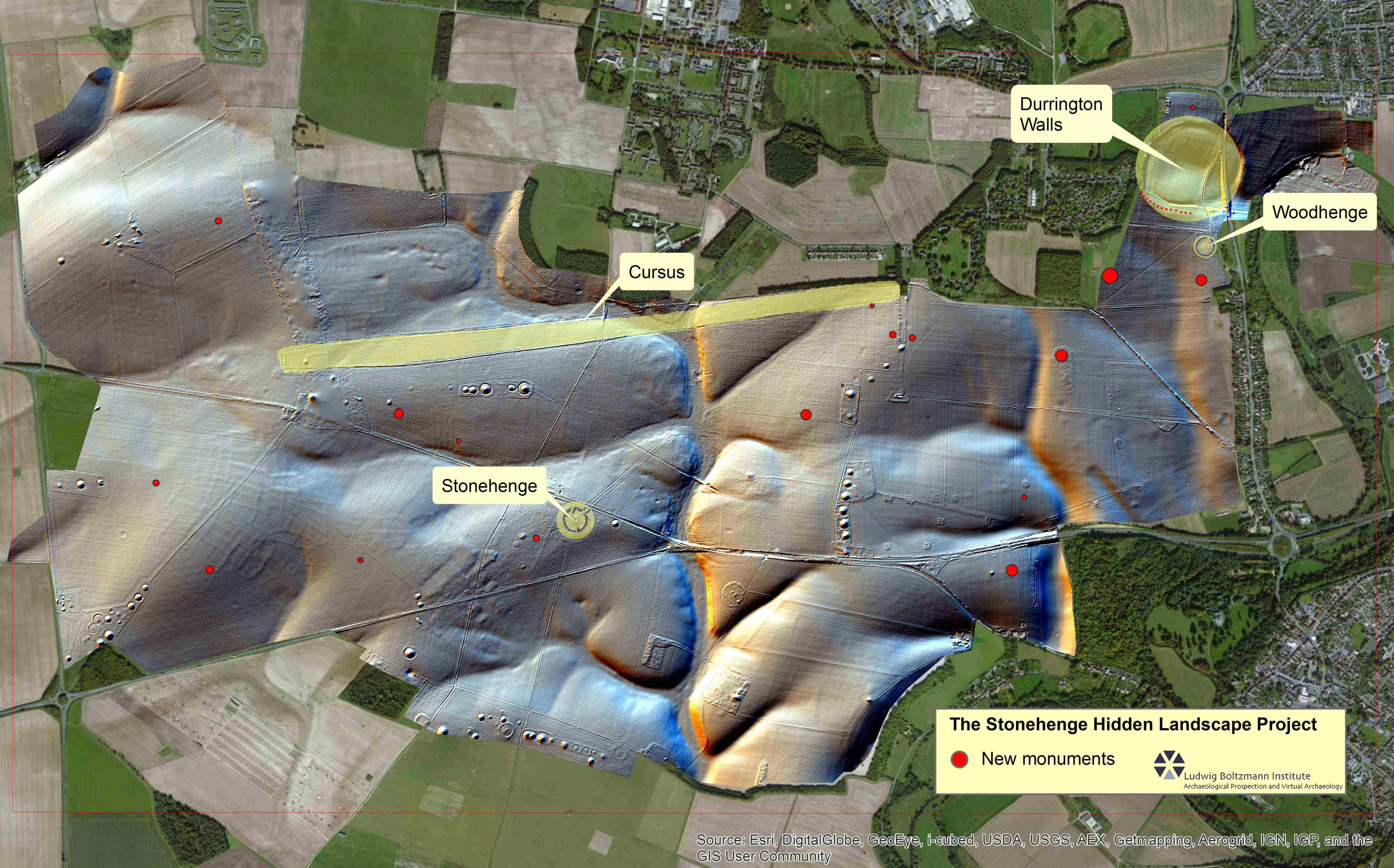

The Stonehenge Hidden Landscapes Project team, using non-invasive geophysical prospection and remote sensing technologies, has now discovered evidence for a row of up to 90 standing stones, some of which may have originally measured up to 4.5 metres in height, Many of these stones have survived because they were pushed over and the massive bank of the later henge raised over the recumbent stones or the pits in which they stood. Hidden for millennia, only the use of cutting edge technologies has allowed archaeologists to reveal their presence without the need for excavation.

At Durrington, more than 4.5 thousand years ago, a natural depression near the river Avon appears to have been accentuated by a chalk cut scarp and then delineated on the southern side by the row of massive stones. Essentially forming a C-shaped ‘arena’, the monument may have surrounded traces of springs and a dry valley leading from there into the Avon. Although none of the stones have yet been excavated a unique sarsen standing stone, “The Cuckoo Stone”, remains in the adjacent field and this suggests that other stones may have come from local sources.

Previous, intensive study of the area around Stonehenge had led archaeologists to believe that only Stonehenge and a smaller henge at the end of the Stonehenge Avenue possessed significant stone structures. The latest surveys now provide evidence that Stonehenge’s largest neighbour, Durrington Walls, had an earlier phase which included a large row of standing stones probably of local origin and that the context of the preservation of these stones is exceptional and the configuration unique to British archaeology.

This new discovery has significant implications for our understanding of Stonehenge and its landscape setting. The earthwork enclosure at Durrington Walls was built about a century after the Stonehenge sarsen circle (in the 27th century BC), but the new stone row could well be contemporary with or earlier than this. Not only does this new evidence demonstrate an early phase of monumental architecture at one of the greatest ceremonial sites in prehistoric Europe, it also raises significant questions about the landscape the builders of Stonehenge inhabited and how they changed this with new monument-building during the 3rd millennium BC.

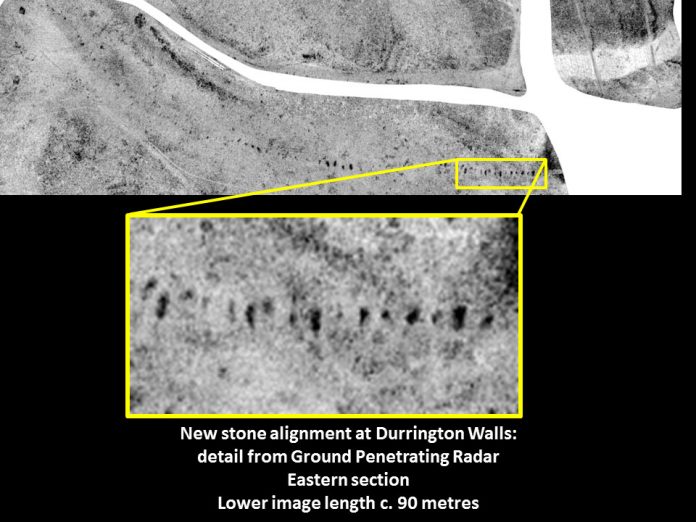

High resolution ground penetrating radar data

The Stonehenge Hidden Landscapes Project is an international collaboration between the University of Birmingham and the Ludwig Boltzmann Institute for Archaeological Prospection and Virtual Archaeology (LBI ArchPro) and led by Professor Wolfgang Neubauer and Professor Vincent Gaffney (University of Bradford). As part of the project, experts from many different fields and institutions have been examining the area around Stonehenge revealing new and previously known sites in unprecedented detail and transforming our knowledge of this iconic landscape.

“Our high resolution ground penetrating radar data has revealed an amazing row of up to 90 standing stones a number of which have survived after being pushed over and a massive bank placed over the stones. In the east up to 30 stones, measuring up to size of 4.5 m x 1.5 x 1 m, have survived below the bank whereas elsewhere the stones are fragmentary or represented by massive foundation pits,” says Professor Neubauer, director of the LBI ArchPro.

“This discovery of a major new stone monument, which has been preserved to a remarkable extent, has significant implications for our understanding of Stonehenge and its landscape setting. Not only does this new evidence demonstrate a completely unexpected phase of monumental architecture at one of the greatest ceremonial sites in prehistoric Europe, the new stone row could well be contemporary with the famous Stonehenge sarsen circle or even earlier,” explains Professor Gaffney.

“The extraordinary scale, detail and novelty of the evidence produced by the Stonehenge Hidden Landscapes Project, which the new discoveries at Durrington Walls exemplify, is changing fundamentally our understanding of Stonehenge and the world around it. Everything written previously about the Stonehenge landscape and the ancient monuments within it will need to be re-written,” says Paul Garwood, Senior Lecturer in Archaeology at the University of Birmingham, and the principal prehistorian on the project.

Dr Nick Snashall, National Trust Archaeologist for the Avebury and Stonehenge World Heritage Site, said: “The Stonehenge landscape has been studied by antiquaries and archaeologists for centuries. But the work of the Hidden Landscapes team is revealing previously unsuspected twists in its age-old tale. These latest results have produced tantalising evidence of what lies beneath the ancient earthworks at Durrington Walls. The presence of what appear to be stones, surrounding the site of one of the largest Neolithic settlements in Europe adds a whole new chapter to the Stonehenge story.”

Dr Phil McMahon of Historic England said: “The World Heritage Site around Stonehenge has been the focus of extensive archaeological research for at least two centuries. However this new research by the Hidden Landscapes Project is providing exciting new insights into the archaeology within it. This latest work has given us intriguing evidence for previously unknown features buried beneath the banks of the massive henge monument at Durrington Walls. The possibility that these features are stones raises fascinating questions about the history and development of this monument, and its relationship to the hugely important Neolithic settlement contained within it.”

Project website