For the past two months, I have been taking the paper versions of my data from books, monographs, archaeological field notes, laboratory documents, and excavation reports, and creating a digital database of them that will allow me to conduct spatial and statistical analysis and after five weeks of inputting dataall five cemeteries that are being examined have been transferred to digital versions.

One of the things that leapt out while coding the data, was that there were no specific ages for individuals who were 45 years or more. This doesn’t mean that there weren’t people older than 45, but rather it means that we can’t age individuals older than 45 well.

So instead of stating an age range like 50-55 years, we simply code the individual as 45 or more years old. This renders the elderly invisible ie- we don’t have a full sense of how old individuals are, how bodies change when the individuals are later in age, and how they may be buried with different objects at different later ages.

A new study Cave and Oxenham (2014), argues that the actual age to which people lived in the past may be much higher than previously thought. They argue that the reason people assume that individuals in the past died younger is due to a number of reasons. 1) Average age of death in past communities is often skewed younger due to high childhood mortality reducing the average. 2) Skeletal indicators for old age are less likely to survive in skeletal tissue due to being in areas which are more likely to degrade over time. 3) Age-at-death estimations aren’t as reliable for adults. When we determine age for sub-adults, we can look at development of teeth and bones. However, in adults, they are already developed so we need to look at degradation and wear on bones which can be more highly variable. 4) Finally, for older adults, we often don’t identify an age category- rather we simply use the lowest possible age and code the individual as 50 years or more. The goal of Cave and Oxenham (2014) is to present methods that allow for the elderly to be categorized not in a catchall 50+ years, but to sort them into decades (ex. 50s, 60s, 70s, 80s) to better understand how the elderly in the past are treated in life and death.

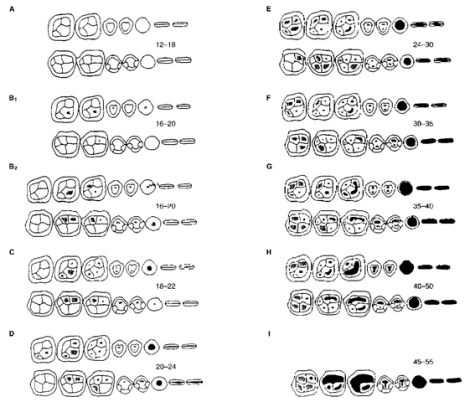

The sample under examination is from the site of Worthy Park, an Anglo-Saxon cemetery dating from middle of the fifth century AD to the middle of the seventh century AD. This site is located near Winchester, Hampshire in the UK. They examined dental wear of 48 individuals from the cemetery. While there are many methods for determining age-at-death, Cave and Oxenham (2014) focus on occlusal tooth wear for age estimation as tooth wear is significantly correlated with age. The first and second molars are examined because they are the most reliable for estimating age from wear. Once wear has been estimated for each individual, individuals are seriated from least to most amount of wear. In addition to this, they compare the sample against a known age-at-death population to get a better understanding of dental wear and age.

Based on the new estimation for age-at-death based on dental wear, Cave and Oxenham (2014) are able to create a more realistic mortality profile of the population. They compare their age estimations to the original estimations of the cemetery which didn’t age any individuals in categories over 50 years (listed as 50+ years). They determined that there were 5 individuals who were 45-54, 7 who were 55-64, 8 who were 65-74, and 7 who were 75-85 years old. Based on this, they conclude that using categories like “50+ years” hides variation in the older adult population and aids in the misconception that historic populations didn’t live long. They argue that we need to stop using catchall age categories and start representing the range of age-at-death more appropriately.

Of course, they do not that there are some issues with this type of age estimation and that it isn’t 100% accurate. Different people will wear their teeth in different ways due to social status and access to different types of food. However, in general, this provides an important method for better understanding the older adult population. By better ageing older individuals, we can create more appropriate interpretations of how individuals in the past were treated based on their age. There is a major difference between a 50 year old and an 80 year old that cannot be ignored simply because our methods aren’t as reliable and it is easier to code as 50+. If you get the chance, I would highly suggest reading this paper for more details on their method!

Works Cited

![]() C. Cave, & M. Oxenham (2014). Identification of the Archaeological ‘Invisible Elderly’: An Approach Illustrated with an Anglo-Saxon Example International Journal of Osteoarchaeology, Early View

C. Cave, & M. Oxenham (2014). Identification of the Archaeological ‘Invisible Elderly’: An Approach Illustrated with an Anglo-Saxon Example International Journal of Osteoarchaeology, Early View

Nederfrederiksmose Man 1898 (crop)

Nederfrederiksmose Man 1898 (crop)